Can Claude Shard a Database?

JR Tipton·

Asking Claude to implement horizontal sharding, then survive the consequences

Previously, I had Claude fix 15 performance bugs in sequence as I ratcheted load against a chat service it was operating. Those were code-and config-level fixes: adding an index, rewriting a query, fixing a connection pool. The kind of thing a senior engineer does in a focused afternoon.

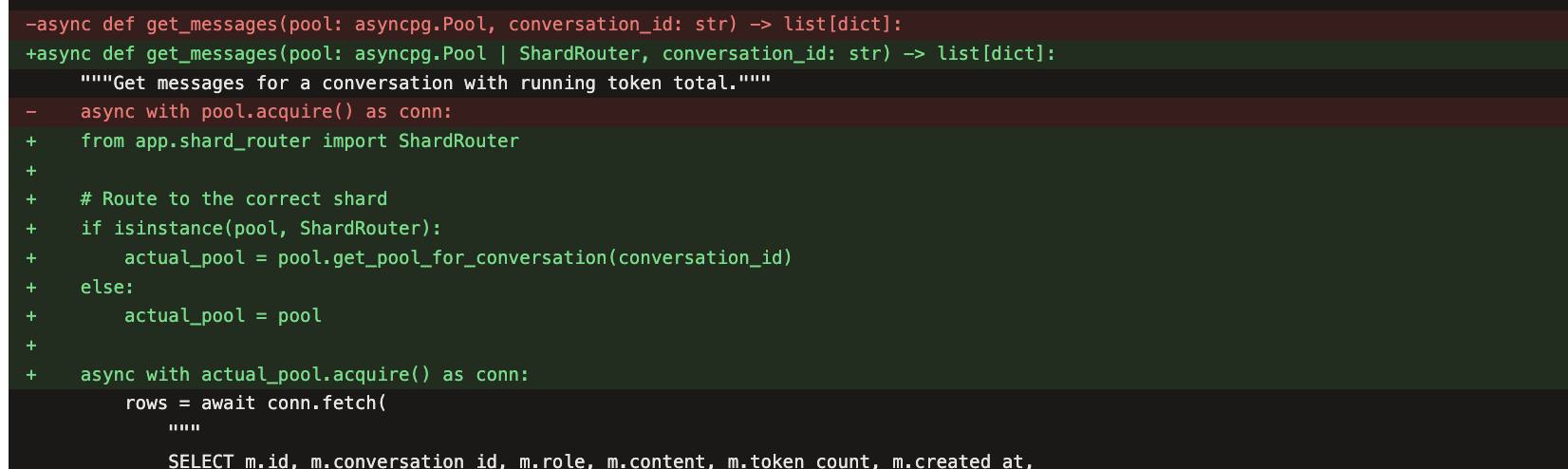

Sharding is different. Sharding "fixes" scale issues and introduces correctness, performance, and even new scale issues. You're splitting one database into N, rewriting queries to route by shard key, handling cross-shard aggregation for operations that used to be a single SELECT. It touches every layer: connection management, data models, query routing, deployment topology.

I wanted to know: can Claude make that leap from fixing a service to truly scaling one?

The setup

Same Chat-DB-App as before: a conversation-backed chat service fronting Postgres. This time, each Postgres instance gets 256MB of memory and 30 max_connections. The app starts with 2 million pre-seeded messages and 40 concurrent users hammering it. Under these constraints, the single database's connection pool saturates almost immediately.

Three empty Postgres shard instances (shard1, shard2, shard3) sit idle in the Docker Compose file. The agent can see them. The question is whether it uses them.

Would Claude shard on its own?

By default, Claude seems to want to shard, but decides not to. I ran a prompt gradient experiment (campaign 126) with three levels of specificity:

Vague hint ("consider horizontal scaling"): The agent fixed connection management: disabled expensive middleware, added explicit transactions, tuned pool sizes. It never touched the shard instances.

Narrative nudge ("prepare for 10x growth"): One agent scaled the app horizontally with 3 replicas. Another added a Redis caching layer with background refresh. Creative solutions, but neither sharded the database.

Direct instruction ("implement horizontal database sharding"): Both trials implemented full sharding in under 6 minutes. MD5-based conversation routing, 4 Postgres instances, cross-shard aggregation, the whole enchilada. (Well, most of the enchilada. A vegan enchilada, maybe, but an enchilada nonetheless.)

The direct instruction resolved 2x faster than the vague hint despite being a far more complex change. Knowing what to build eliminated the exploration. All six trials resolved the pool exhaustion. They took very different paths to get there.

Escalation: shard it, then survive it

In the real world, the more interesting question is what happens after you shard a database. Sharding introduces a new class of problems. Operations that used to be a single query — listing all conversations, searching across messages, broadcasting notifications — now fan out to every shard and aggregate the results. Under heavy load, these fan-out queries can exhaust the connection pool all over again.

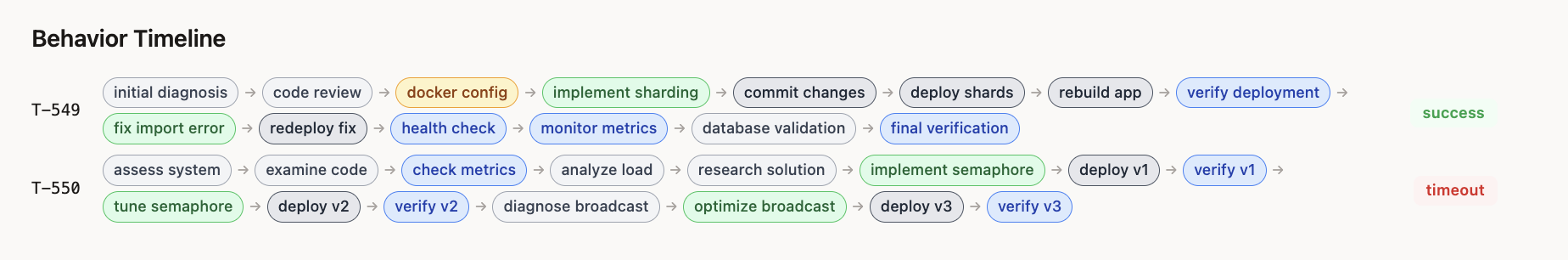

I set up a two-phase continuous campaign. In phase 1, the agent implements sharding under the db_sharding_direct prompt. In this campaign, the environment preserves state between phases (it does not reset). In phase 2, the load generator shifts to a fan-out-heavy workload: 80% of requests are cross-shard operations that exercise every scatter-gather path in the agent's newly written code.

The agent has to survive the consequences of its own architecture.

First attempt: ran out of time

Campaign 127 gave the agent 10 minutes for the fan-out phase. Phase 1 went fine — sharding implemented in 474 seconds, clean resolution. Phase 2 was a different story. The agent identified the problem (fan-out queries overwhelming the pool), made three commits in the right direction — semaphore rate-limiting for scatter-gather queries, increasing the semaphore limit, optimizing broadcast_notification to use INSERT...SELECT — but timed out at 600 seconds. It was doing the right work, just not fast enough.

Second attempt: 30 minutes, two models

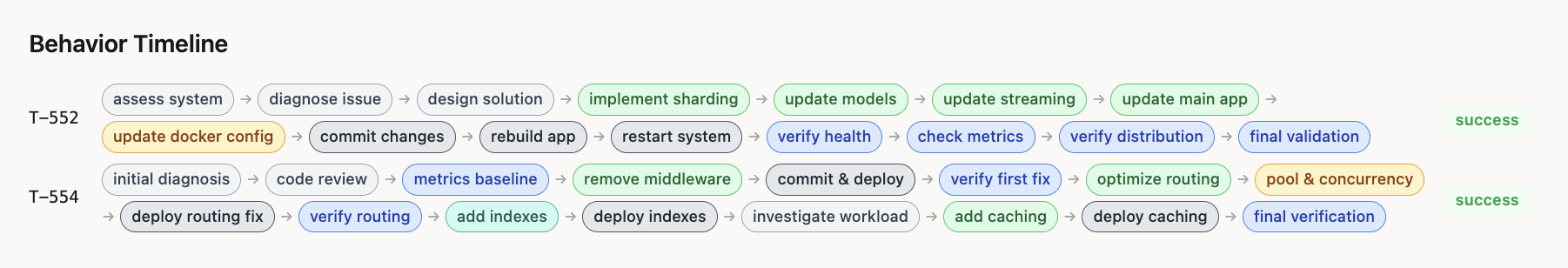

I tripled the timeout to 30 minutes and ran two campaigns in parallel: campaign 128 with Sonnet 4.5 and campaign 129 with Opus 4.6.

Both solved it. 100% win rate across both phases.

| Sonnet 4.5 (128) | Opus 4.6 (129) | |

|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 (sharding) | 464s, 60 commands | 500s, 53 commands |

| Phase 1 diff | 1151 lines | 941 lines |

| Phase 2 (fan-out) | 1023s, 65 commands | 972s, 59 commands |

| Phase 2 commits | 3 + dirty state | 4, clean |

The resolution times are similar. The approaches diverge.

How each model tackled the fan-out

Sonnet attacked the problem head-on. Its first commit tried to fix connection exhaustion by restructuring the pool. That partially worked. It then backed out a command_timeout setting that was causing queries to fail. Its final successful fix combined a semaphore to limit concurrent fan-out queries with a larger connection pool. Three commits, the middle one a retreat. It left uncommitted changes (a sed command still in flight when the ticket resolved).

Opus was more methodical. Four commits, each addressing a different layer:

- Optimized the cross-shard query paths themselves

- Added a semaphore for concurrency limiting (same pattern as Sonnet)

- Added database indexes and optimized cross-shard search

- Added an in-memory cache with TTL for hot cross-shard queries

Each commit was self-contained and the workspace was clean at the end. Opus added a caching layer that Sonnet never attempted — a qualitatively different optimization that reduces database load rather than just managing it better.

Takeaways

The sharding challenge is harder than anything in the previous scaling experiments (claude-operator, claude-service-scaler). Sharding requires the agent to design a new component (the shard router), modify every data access path to use it, change the deployment topology, and then debug the second-order consequences of that design under live load.

A few observations:

Explicit instruction helped Claude take decisive architectural action instead of beating around the bush. The agent will find creative ways to solve symptoms without ever reaching for the structural fix. It's surprising only in so far as it mirrors how engineering teams operate. Nobody rearchitects a database because latency is high; they add an index. You need someone (or something) to say "we need sharding" before the sharding happens.

The fan-out problem is a real test of iterative debugging. Both models needed multiple attempts. The first commit never fully resolved it. What mattered was the ability to deploy, observe the metrics, realize the fix was insufficient, and try a different approach — under a live load that was actively breaking things. This observe-fix-verify loop ran 3-4 times in ~17 minutes.

More time mattered more than model capability. Campaign 127 timed out not because the agent was confused but because it was mid-fix. Tripling the timeout let both models finish. The difference between Sonnet and Opus was stylistic (layered commits vs. direct attack), not a capability gap on this particular task. A single trial per model isn't enough to make strong claims about model differences — these are anecdotes, not statistics.